The Way of the Independent Artist

The internet is a blessing for the independent creative. It gives us distribution, reach, control over how our work is presented. It also gives us freedom to do the work we most want to do. Having rejected the false notion of success, I have after some years arrived at a pattern of productive activity which I find sustainable.

First and foremost, I get regular time where the phone is off and the mail is left unopened while I work creatively on new stuff, or garden the back catalog. I might stay in the studio, or walk with a notebook, or take a guitar to the woods, but it’s my time to think and to exercise my imagination.

Then there are collaborative creative sessions with other people, which I love, gigs, events, shows, and keeping abreast of culture, which is important since that’s the field I work in. Other times, I’m calling people on the phone, developing projects, writing articles like this, editing video and audio, organising productions, work for regular clients.

Then there’s life, love and cooking. It’s a good rhythm and it works for me.

Growing up and finding your place in the many-faceted worlds which are the creative industries is a task which until recently was left almost entirely to chance. Especially in the UK, there is very little education – notable exceptions being the Croydon’s Brit School and Liverpool’s IPM and only very recent government initiatives to assist in creative career-building

For an independent songwriter musician, there’s never been a better time to get your music out there and find your audience. Avenues to revenue are changing radically, and internet business is changing all the time, which I find very exciting. We can license our own work, set the price and collect revenue ourselves, with tiny overheads, courtesy of Sir Tim. Sure, we lack the marketing power of a multi-million dollar corporation, but that doesn’t mean we can’t find an appreciative audience, and make a living. We might not be able to get into the high streets that easily, but we can certainly get into the living rooms, the pockets and the hearts of our audience.

I make money from music, but I’m very grateful for having other talents which mean I don’t have to rely solely on music for income. I’m with composer Charles Ives who believed that if you were writing with your eye on the balance sheet, it was bad for your family, and bad for music.

We can emulate Hogarth who used the modern technology of his day to make a small fortune from his prints and get through life without a patron, largely pleasing himself.

On a business level, it’s also my preferred way of working. Half my family have been print technicians, running their small business, or working for bigger ones. My press is the internet, and I am a journalist as well as publisher, as well as a creative writer, video maker and musician.

On a personal success level, my advice to any artist, young or old, talented or hopeless, is this:

On a personal success level, my advice to any artist, young or old, talented or hopeless, is this:

So long as your family isn’t starving, and there’s a roof over your head, and you’re not doing anyone any harm, just crack on with amusing your muses.

Call whatever you decide to do “work” and then work until people take you seriously.

Look out for things that might stop you working – like, poverty, illness, jealousy, envy, drugs, dodgy dealings, badly-maintained cars – and avoid them.

Be nice to people, get help when you need it.

Keep going. Make friends. Dress up. Don’t be distracted. Do your best.

Consign wankers to the mental dustbin and pay them no attention unless it is to remove them to the karaoke bar.

Remember the wise words of The Residents: “Ignorance of your culture is not cool”

Keep your feet on the ground and your eyes and ears open.

If you see paparazzi, photograph them.

If you become famous, remember you’re a Womble

Keep going, try not to be ripped off, don’t forget the milk.

In 1998 I was recovering from exhaustion, clinical depression and a long-term relationship breakup, feeling bleak, despondent and wasted. I hadn’t much to give. Enter Mick Martin, one of the most creative people I have ever met. Possessed of a profound and subtle musical sensibility, Mick had been part of the trio of

In 1998 I was recovering from exhaustion, clinical depression and a long-term relationship breakup, feeling bleak, despondent and wasted. I hadn’t much to give. Enter Mick Martin, one of the most creative people I have ever met. Possessed of a profound and subtle musical sensibility, Mick had been part of the trio of  Mick would never use his relationship to his famous brother for self-aggrandisement, or even (it sometimes seemed to me) perfectly logical advancement. If anything, having a famous brother made Mick wiser to the downside of the music business and conscious that he must tread his own path to succeed. Having brothers myself, I could understand that. But despite this caution, we did get to trade favours with Vince, and together we worked on material for Vince’s side project

Mick would never use his relationship to his famous brother for self-aggrandisement, or even (it sometimes seemed to me) perfectly logical advancement. If anything, having a famous brother made Mick wiser to the downside of the music business and conscious that he must tread his own path to succeed. Having brothers myself, I could understand that. But despite this caution, we did get to trade favours with Vince, and together we worked on material for Vince’s side project

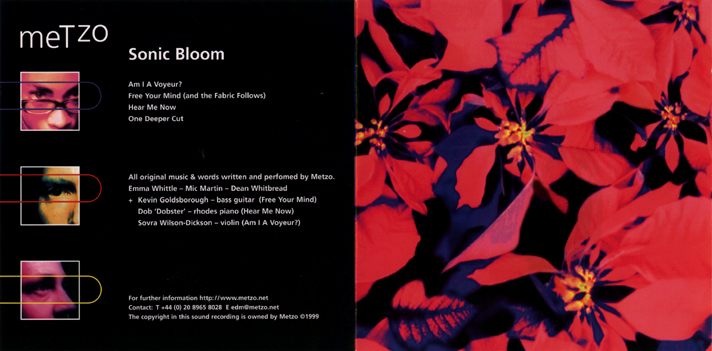

Happily, Mick and Emma liked this idea, and the production went well. The icing on the cake was musician

Happily, Mick and Emma liked this idea, and the production went well. The icing on the cake was musician

It was all lots of fun and quite promising. Ross came on tour with my scratch band to Palermo, Sicily. Unfortunately, we also took his friend the snide sax player, who decided to play on Paul’s paranoia and having taken the money and enjoyed the gig, bitched on his return that I had been scornful of Paul’s lack of experience and had publicly demeaned him. I hadn’t, of course, but nonetheless, a schism ensued as intended, and thus ended a fertile period which could have gone further.

It was all lots of fun and quite promising. Ross came on tour with my scratch band to Palermo, Sicily. Unfortunately, we also took his friend the snide sax player, who decided to play on Paul’s paranoia and having taken the money and enjoyed the gig, bitched on his return that I had been scornful of Paul’s lack of experience and had publicly demeaned him. I hadn’t, of course, but nonetheless, a schism ensued as intended, and thus ended a fertile period which could have gone further. I don’t carry any regrets or grudges, indeed, the opposite is true. I am still proud of some of the songs, particularly those which came from my lending Paul some classic Zappa, which he loved, and promptly looped. I thought so much of it that I even took it to Los Angeles in December 1993, and set up an audience with Frank’s lawyer to license the use of his music in this song. But in this endeavour, time was against me. I was mid-deal when Frank Vincent died on December 4th. Few people knew how desperately ill he was, and it was a shock when he died tragically young, having left a huge legacy and inspired more bands and individuals than you would know.

I don’t carry any regrets or grudges, indeed, the opposite is true. I am still proud of some of the songs, particularly those which came from my lending Paul some classic Zappa, which he loved, and promptly looped. I thought so much of it that I even took it to Los Angeles in December 1993, and set up an audience with Frank’s lawyer to license the use of his music in this song. But in this endeavour, time was against me. I was mid-deal when Frank Vincent died on December 4th. Few people knew how desperately ill he was, and it was a shock when he died tragically young, having left a huge legacy and inspired more bands and individuals than you would know.