There are certain things I know. One of them is when I have gone far enough down a certain path and must turn back. Responding to this is difficult only when people are following and the path is narrow. In which case, I might have to leave the path entirely in order to get back to where I need to be going without treading on people's toes.

Another is when I should stand up to an accuser. Sometimes, I just need to remind myself not to give a flying fuck, no matter how intrusive, misguided or hateful the words, and to remember that whatever it is that weighs them down need not be any major concern of mine, however bad I might be already feeling about my own sins, past or present, real or imaginary, connected to them or not. Another one is that sometimes, no matter how innocent you actually are, or whether you meant to do harm, you should simply apologise if harm was the outcome.

I recall how focused I was when I was at art college, and the day-to-day glorious absorption of the time. Ideas and techniques flowed freely and unjealously from person to person, space to space, evenings and mornings were communal experiences of discovery, books were passed around like joints, and this shared experience created a living fabric of experimentation and expression. In this environment I thrived, learning, tasting and testing new things, passing on as much as I came to know. The majority of that learning was gained from my peers, as one particularly bright and sensible tutor, Norman Brown, pointed out one fine, sunlit morning, factory glass reflecting the fringe of his words with his scraggly rollup cigarette, inspiring me with his unabashed honesty.

From a starting point of clumsy social skills but quick intelligence, making many false starts I grew in confidence while at Middlesex, and as I did so, within a term or two lost an almighty dose of the ruinous self-doubt which had hitherto prevented me from expanding my heart, my mind and my prospects. For the first time in my life I was able to simply be, for good and bad, and my spontaneous self emerged blinking and mostly smiling. I started to glow with the red-orange of the sodium streetlights, which I had spent the preceding years oil painting into my semi-urban night landscapes.

One September day it was my fellow housemate Graham Gussin's birthday, and I took it into my head to create a large birthday card for him in primary colours. Although he hardly used his allocated workspace except to meet tutors and discuss earnestly with them the meaning of meaning and the poetry of poetry, sharing trendy brown licorice-flavoured cigarette papers, he was in college that day, and in my extravagant and affectionate way I wanted to amuse him and celebrate. I took an A3 piece of paper and some water-based acrylic paints to his space, and proceeded to paint there, in a deliberately naive and supposedly comic fashion a horse - a very bad horse - upon which I wrote, "A GeeGee for G.G." Ha ha ha. Satisfied with my tribute, I grabbed a coffee, and returned to my more serious endeavours in my own space a thirty or so yards away.

Twenty minutes later I became aware that Annie, one of the cute art students in my year, was upset. She was being comforted as she sat sobbing, bright, visible tears dripping off her nose, splashing onto the paint-spattered concrete.

What was up, I asked her female friend, and to my surprise got nothing but a filthy look.

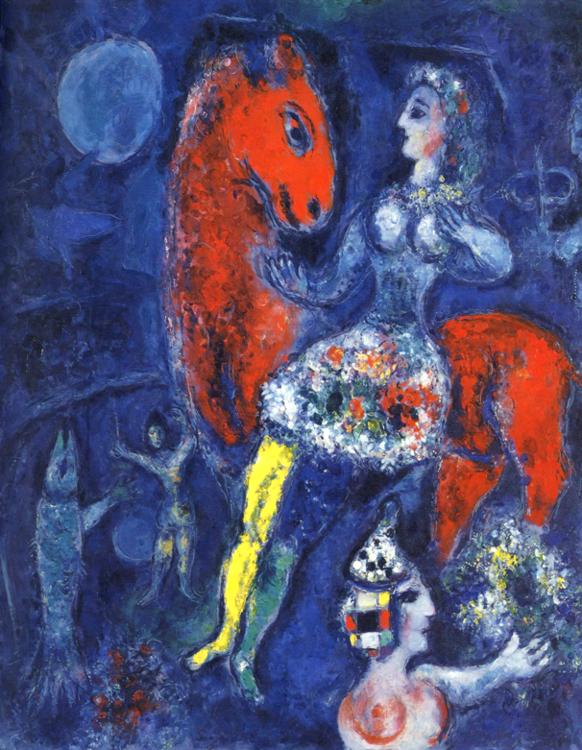

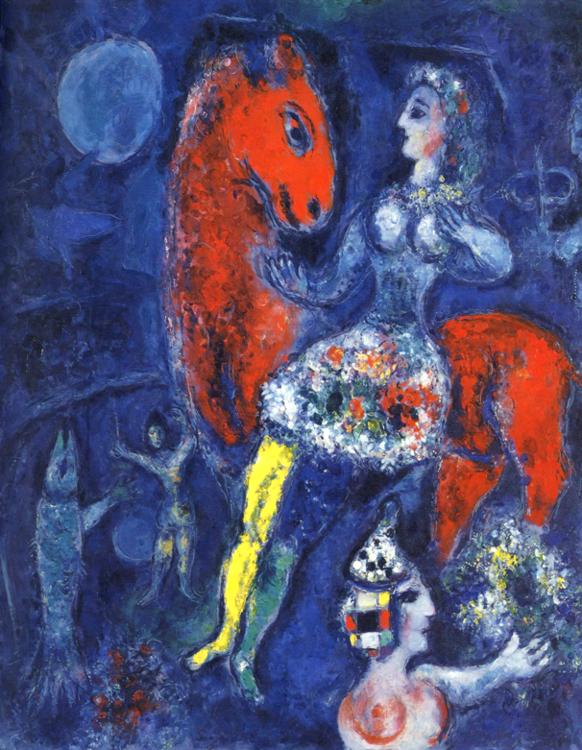

Perturbed I ventured nearer and discovered that Annie had interpreted my entire horse-painting episode as direct mockery, an out-of-the-blue, unwarranted personal attack upon her personally. The fact that I didn't even see that she was there as I gaily painted my birthday card was lost upon her. I had only vaguely noticed that she had been painting horses for the past few weeks, inspired by Chagall. I did not know how insecure pursuing her muse had made her feel over the preceding months, surrounded by clever, intellectual, Guardian-reading students who had sneered at her simple representationalism - I wasn't one of them. She didn't figure in my scene, I barely knew her, except to say hi, and admire her curves.

I really was aghast. Did she really think I was singling her out for some kind of mocking plagiarism? What kind of person would I have to be to be able to enact such an elaborate stunt? She was of course the centre of her own universe, but who was I to know how low she had fallen, crouched into her defensive posture?

I stumbled through my explanation, which, sincerely given, did much to reassure her. Annie was a good-natured girl, and we made up easily, with her laughing at herself. I was glad of it and always had a soft spot for her afterwards.

To be so misinterpreted that day has stuck with me ever since. I can still remember the sick feeling of guilt which fell upon me like a winter coat. When it has happened since, I remember Annie and her quick kindness, she who taught me the lesson of forgiveness for imagined slights, and showed me how blind one can be to other people's sensitivities, especially when on some single-minded mission which has no reference or relevance to them.

But the injustice of being singled out for having done wrong when no wrong has been done has always sat badly with me, and even though the lesson of apologising even though the mistake was made elsewhere is a valuable one, kept on the shelf alongside the twin tomes, "Fuck It" and "Fuck Off", sometimes I'm still torn between which pages to turn, and even whether to read the book, or simply, like a Paris surrealist, to throw it, aiming for the head.

I found myself in Place Émile Goudeau, a blessed space surrounded by tourists and film crews and sun. I sat and breathed in this shadowed pause, letting the city sink in to my old London bones, before climbing steadily up through the tourist trap which surrounds the Basilica of the Sacré Cœur.

I found myself in Place Émile Goudeau, a blessed space surrounded by tourists and film crews and sun. I sat and breathed in this shadowed pause, letting the city sink in to my old London bones, before climbing steadily up through the tourist trap which surrounds the Basilica of the Sacré Cœur.

I must share with you the album I am most enjoying right now. I've played some of the tracks from this excellent compilation on

I must share with you the album I am most enjoying right now. I've played some of the tracks from this excellent compilation on